Dr. E Vickers (with additional contributions from E Mwesigwa) | Pharmacentral.com

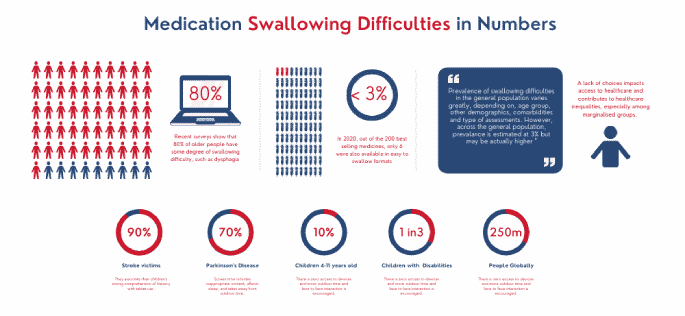

Individuals with swallowing difficulties face inequalities in their access to safe medicines and could be at a greater risk of poor health outcomes compared with the general population. This article sets out to highlight the scale of the problem and suggests actions that the pharmaceutical industry and regulators can take to improve the situation.

What are Swallowing Difficulties?

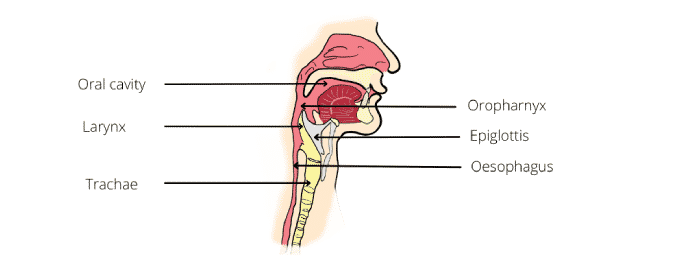

Swallowing, the act by which we ingest solid food, liquids or medication, is in fact a highly intricate process that requires the interplay of several nerves and muscles in the oral cavity, pharynx and oesophagus in order to safely transfer bolus into the stomach.

While the vast majority of us do this simple act without much thought, there are millions of people who, for one reason or another, struggle to swallow. For them, the ability to initiate and complete a normal swallow is tortuous, accompanied by anxiety, pain, choking or aspiration.

Swallowing disorders occur in all age groups, either as a result of congenital abnormalities, damage to structures in the oropharyngeal anatomical structures and or short-term or long-term medical conditions. In some age groups and populations, however, swallowing difficulties are far more significant and pernicious. For example, in children with learning disabilities as well as senior citizens who need daily medication to alleviate their conditions.

In some situation, an inability to swallow solid medication can be a matter of life and death. For instance, in those with Parkinson’s disease where 70-80% of sufferes have swallowing problems or those who have had a stroke, where swallowing difficulties run at 90%.

Read about our article on Empathy – What the pharmaceutical industry can learn from the IT Industry

The main causes of swallowing difficulties catalogued in the medical literature include:

- Dysphagia, the most well-known among swallowing disorders, refers to a group of disorders characterised by changes in the structures or neurological control of the swallow. Studies show that dysphagia affects 3 % of the general population.

- Odynophagia which refers to pain swallowing caused by irritation or infection of the oral mucosae and oesophagus, particularly in individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, oesophagitis or disorders of motility of the oesophagus.

- Phagophobia which is the fear and avoidance of swallowing foods, liquids or medication, usually based on the person’s fear of choking. It is on a psychological dimension and characterized by swallowing complaints but no abnormalities upon physical examination or investigation.

Note that difficulty to swallow is not in itself a disease, rather it may be an indication of an underlying structural, neurological or other dysfunction for which proper medicare should be sought since factors that lead to abnormal swallowing, whether it is dysphagia, odynophagia or phagophobia, can be life limiting, and if severe, life threatening.

Anatomy and Physiology of Swallowing

The normal swallow permits an individual to handle a wide range of solid and liquid products of varying volumes, textures and consistencies. This process can generally be divided into different phases, depending on whether the material is a liquid or a solid.

But first, it is essential to quickly review the anatomy and physiology of swallowing as a basis for appreciating swallowing difficulties and how to design effective interventions.

The anatomy of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx and the innervations of the muscle in the oral cavity are shown in the figure below:

The tongue has both oral and pharyngeal surfaces. The oral cavity is separated from the pharynx by the faucial pillars. The pharynx has a layer of constrictor muscles that originate on the cranium and hyoid bone, and the thyroid cartilage anteriorly.

Note that the anatomy of the head and neck of infants is different from that of adults. In infants, teeth are not erupted, the hard palate is flatter, and the larynx and hyoid bone is higher in he neck to the oral cavity. The epiglottis touches the back of the soft palate so the larynx is open to the nasopharynx, but the airway is separated from the oral cavity by a soft tissue barrier.

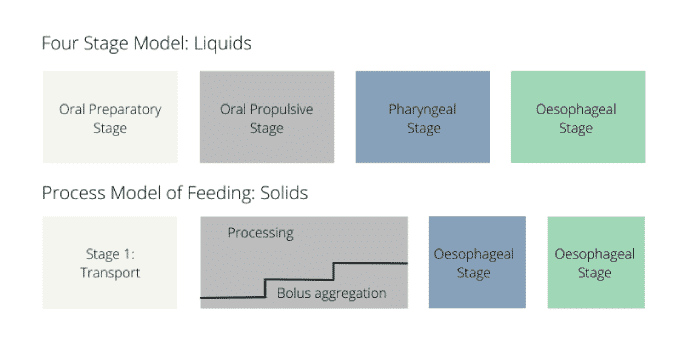

The physiology of normal eating and swallowing is described by two models: the four stage model for liquids and the process model for solids.

Although there are differences in the sequence of events in the two models, it is possible to reduce the swallow to three main phases as follows:

Oral Phase

Upon introducing a liquid or solid into the mouth, the material is prepared into a bolus and or transported to the middle of the tongue. During this stage, the posterior part of the oral cavity will be sealed by the action of the soft palate and tongue, thus preventing premature leakage of bolus into oropharynx before the swallow. Note that the tendency for leakage increases with age.

After a brief moment the anterior tongue rises, touching the alveolar ridge of the hard palate just behind the upper teeth. The posterior tongue drops, opening the back of the oral cavity. The surface of the tongue lifts upward, propelling the bolus back along the palate and into the pharynx.

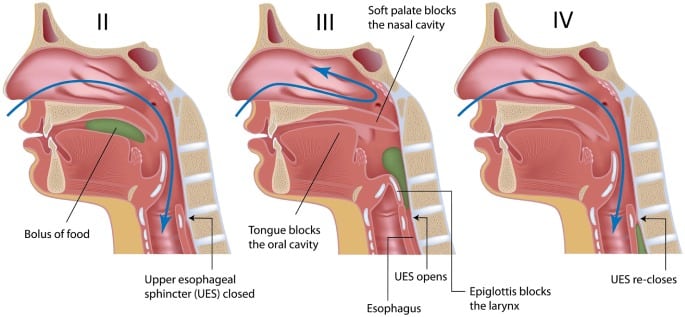

Pharyngeal Phase

The pharyngeal swallow is a swift activity that follows the oral phase. It serves two main purposes:

(1) to permit bolus to be propelled through the pharynx and the upper oesophageal sphincter and into the oesophagus, and

(2) to protect the airway by preventing entry of food into the larynx and trachea.

In this phase, the soft palate elevates and contacts the walls of the pharynx, leading to the closure of the nasopharynx at the point the bolus hurtles into the pharynx. The base of the tongue retracts, pushing the bolus against the pharyngeal walls. Constrictor muscles of the pharynx then contract, squeezing the bolus downward, and together with retraction of the base of the tongue, pushes the bolus downward.

For obvious reasons, the ability to safely pass bolus through the pharynx without aspirating or regurgitation into the nasal cavity is important in human swallowing. Therefore, there are several mechanisms at play which the body uses to prevent entry of food particles into the airway during swallowing.

Oesophageal Phase

The oesophageal phase describes the transport of the bolus through the oesophagus. The oesophagus is a tube-shaped structure originating from the lower part of the upper oesophageal sphincter and terminating at the lower oesophageal sphincter.

During the swallow, the muscles relax allowing the bolus to pass down. Movement is facilitated by a series of peristaltic waves, as well as gravity, both of which effectively transport the bolus through lower oesophageal sphincter and into the stomach.

Swallowing Abnormalities

Abnormal swallowing can result from a wide range of conditions and disorders related to the anatomy and or physiology or the oral, pharyngeal and oesophageal dysfunction.

Swallowing difficulties manifest in different ways, which include:

- Painful chewing or swallowing

- Dry mouth (Xerostomina)

- Difficulty controlling solids or liquids in the mouth

- Hoarse or wet voice quality

- Coughing or chocking before, during or after swallowing

- Feeling of obstruction (globus sensation)

Dysphagia

Dysphagia arises from abnormalities in structure or motility and ranges from inability to initiate swallowing to solids getting stuck in the oesophagus.

Generally, two main types of dysphagia are recognised:

Oropharyngeal dysphagia, whereby patients are unable to transfer food into the oesophagus by swallowing. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is subdivided into structural/obstructive and neurological/propulsive.

From a clinical point of view, any difficulties swallowing solids indicates either structural or propulsive oropharyngeal dysphagia, while difficulty swallowing liquids indicates propulsive or neurological oropharyngeal dysphagia.

Oesophageal dysphagia is when patients can initiate swallowing process however as the food passes down the oesophagus and into the stomach, they experience discomfort. The underlying causes can also be structural or propulsive abnormalities.

The table below lists some of the most common causes of oral and pharyngeal dysphagia

Common Causes of Oral and Pharyngeal Dysphagia

| Neurological disorders and stroke | Structural lesions | Psychiatric disorders |

| Cerebral infarction

Brain-stem infarction Intracranial haemorrhage Parkinson’s disease Multiple sclerosis Motor neurone disease Poliomyelitis Myasthenia gravis Dementias |

Thyromegaly

Forestier’s disease Congenital web Zenker’s diverticulum Ingestion of caustic material Neoplasms |

Psychogenic dysphagia

Polymyositis

Connective tissue diseases: Polymyositis & Muscular Dystrophy

Iatrogenic Causes: Surgical resection Radiation fibrosis Medication |

From: Palmer Jb et al, 2006. In Braddom R (ed): Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Elsevier, Philadelphia. Pp 597-616.

Odynophagia

Odynophagia is the disorder in which swallowing is associated with pain. It differs from dysphagia, which is simply difficulty when swallowing — and does not associate with pain, whereas odynophagia always does.

Odynophagia can be caused by infective and non-infective inflammatory processes, benign and malignant esophageal disorders such as achalasia, gastro-esophageal reflux disease and carcinoma.

Some of the conditions associated with odynophagia include:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- Esophagitis

- Candidiasis

- Esophageal Cancer

Phagophobia

Phagophobia is a relatively rare type of anxiety disorder associated with swallowing. It is often mixed up with pseudodysphagia, which is the fear of choking. The key difference between these two phobias is that individuals with phagophobia are anxious about the act of swallowing whereas those with pseudophagia are afraid that swallowing will lead to choking.

Irrespective, phagophobia and pseudodysphagia can be life limiting, and in the case of medication, life threatening. This is especially the case in the small but significant cohort of individuals, who for reasons still to be known, have phagophobia and pseudodysphagia related to medication.

Unfortunately, the causes of phagophobia are poorly understood and may even be multifactorial, involve past experiences, underlying health conditions or simply learned through observing others who struggle to swallow certain things.

It has been found that individuals who watch others experience difficulties (e.g pain or embarrassment) when swallowing may go on to develop phagophobia.

Finally, phagophobia may occur in the absence of any underlying triggers.

Symptoms of phagophobia include:

- Anticipatory anxieties before ingestion of meals

- The tendency to eat very small mouthfuls or drinking frequently or large amounts of liquids during meals as a way to aid swallowing

- Extreme anxiety and fear at the thought of swallowing

- Panic attacks

- Rapid heart rate and breathing

- Reluctance or avoidance of eating or drinking in front of others

- Sweating

- Switching to an all-liquid diet as a way to alleviate anxiety around swallowing

- Weight loss (skipping medication and exacerbation of illness if related to medication)

Oral Medicines and Swallowing Difficulties

The prevalence of swallowing difficulties varies greatly, including population under consideration, comorbidities and assessment methods. Experts contend that prevalence may actually be greater than published figures would indicate since many patients may not report symptoms.

Generally, 70 – 90% of all seniors have some degree of swallowing difficulty. In certain cases, for instance, Parkinson’s disease and Stroke, swallowing difficulties are the norm, and have been reported to be as high as 90%. According to a recent study, swallowing difficulties run at 3% in the world adult population, but are 10 times higher in those with neurological and or psychological conditions, such as learning disabilities, severe mental illness or dementia.

With oral administration of medication being the most preferred route, the swallowing of solid medication, particularly tablets and capsules, presents specific challenges to anybody with swallowing problems. To make matters worse, solid dosage forms need to be taken with water, which requires the same individuals to control a thin fluid, which complicates matters even more.

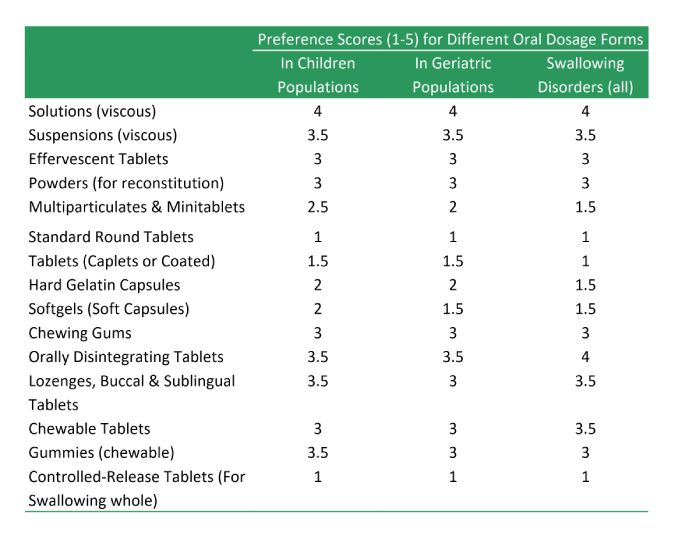

Which medication types are suitable for dysphagia and other swallowing difficulties?

Most medication in use today is formulated as tablet dosage forms. According to the British Pharmacopoeia, a tablet is circular in shape with either a flat or convex faces prepared by compressing the active pharmaceutical ingredients with excipients.

In reality, they are available in a wide range of sizes, shapes, colours and indentations. In addition, tablets may be sugar or polymer film coated as well.

The oral route of drug administration is the most preferred route of taking medicine, and understandably, manufacturers of medicines recognise this. As a result, oral medicines account for more than 70% of all medicines in use.

Tablets (and more specifically, standard compressed tablets) are the single most popular dosage form, responsible for 50% of all pharmaceutical preparations manufactured and sold. Some of the reasons for popularity of tablets include:

- Tablets allow accurate dosage of medicament to be prefabricated and administered simply and conveniently

- Tablets are consistent with respect to weight and appearance

- Drug release rate can be fine-tuned to meet physiological and pharmacological needs of patients

- Tablets can be mass-produced simply and quickly, which allows the wider public to have access to medicines that would otherwise be too costly.

However, to anyone with swallowing difficulties, swallowable tablets are a nightmare. Problems with the neural control or the structures involved in swallowing mean that swallowable tablets are not ideal sufferers of dysphagia. Too big (frankly, most are) and they are a choking hazard. Too small and they become difficult to detect on the tongue and move around in the mouth to initiate a safe swallow.

If the tablets can be crushed beforehand, it can greatly help pass them down however, as with anything that requires precision, the possibility of errors increases with the number of additional manipulations. Thus, having technologies that enable dosing without the need for additional dilution, elaboration or mixing as is always needed in paediatric, geriatric or other swallowing disorders would be of great benefit.

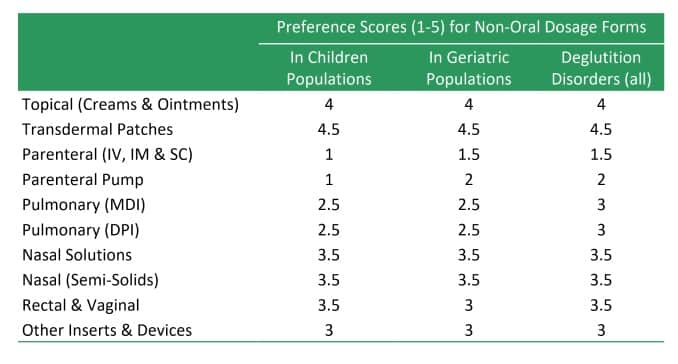

There are alternatives to swallowable tablets, which depending on the type of drug substance and its intended use, may be considered:

- Buccal Tablets

- Caplets and Coated Tablets

- Chewable tablets

- Effervescent Tablets

- Lozenges

- Mintablets

- Multiparticulates

- Orally Disintegrating Tablets (ODTs)

- Powders for reconstitution

- Sublingual Tablets

- Hard Gelatin Capsules

- Soft Gelatin Capsules

- Chewing Gums

- Gummies

- Topical Products (Ointments, Creams, Lotions and Transdermal Patches)

- Parenteral Products

- Inhalation Products

Key Characteristics of Different Tablets Types

| Type of tablets | Description and Advantages | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Swallow Tablets | The vast majority of tablets fall in this category. These tablets are designed for per-oral administration by swallowing | Most tablets belong to this category. They are designed to be swallowed whole although some may be crushed/split up to ease ingestion. |

| Buccal Tablets | Buccal tablets are designed to be placed under the cheek mucosa or between the lip and gum. Typically designed for slow release and absorption. | Buccal tablets permit administration without the requirement for water/swallowing Drugs should not be bitter or unpleasant in the mouth Usually very small and flat and do not require addition of a disintegrant |

| Sublingual Tablets | Sublingual are designed to be placed under the tongue. Unlike buccal tablets, they allow rapid absorption through blood vessels under the tongue while avoiding 1st-pass effect. | Sublingual tablets permit administration without the requirement for water/swallowing Drugs should be soluble, typically low dose and not be bitter or unpleasant in the mouth Careful selection of excipients required |

| Orally Disintegrating Tablets (ODTs) | ODTs are designed to rapidly disintegrate on the tongue into a smooth solution or suspension that can be swallowed without the need for water. | Two key characteristics that a dosage form labelled as an ODT must possess is a rapid disintegration time of 30 s or less, and a tablet weight of 500 mg or less |

| Chewable Tablets | Chewable tablets consist of a mild effervescent excipient base which can be chewed and broken down into a smooth consistency which can be swallowed. | To provide fast disintegration and dissolution, the tablet should be designed to be soft or easy to chew. The active drug substance must not be unpleasant to the taste, and frequently, flavours and sweeteners are required. |

Unfortunately, too many products on the market today are formulated with little consideration of those with swallowing difficulties. Products for children are perforce prepared from products designed for adults; and the same applies for the elderly, who often have swallowing problems while also requiring prolonged, non-crushable tablets. In 2020, for instance, out of the 200 best-selling medicines in the United States, only six were offered in easy-to-swallow formats. It is not funny any longer. It is unsafe and something needs to be done soon.

That people have to crush medication in the 21st century so that children and seniors can be treated despite the wide availability of technologies and excipients and knowhow is disgraceful.

Actions needed to reduce inequalities in dysphagia

The prescription remains the most widely used medical intervention today. Yet it is estimated that up to 50 % of all patients prescribed medication fail to take it correctly. This not only leads to waste of resources but could lead to treatment failure and sub-optimal outcomes.

If society is to equitably offer quality healthcare to all, it will be necessary to take a whole person approach, by recognising the many root causes of inequality, and engender system-wide action, from regulators, pharmaceutical companies, patient groups as well as healthcare workers as the immediate contact points for patients.

Here is a range of preventative actions that local areas can take to reduce inequalities and improve health outcomes and the lives of people with mental illness.

1. A better understanding of the scale of the problem

Although dysphagia and other swallowing disorders are widespread, the scale of the problem, especially as it relates to medication, is still poorly understood.

It is generally known that patients, for one reason or another, tend to underreport their problems during contact with healthcare providers. The lack of understanding on the scale of the problem generally hinders society’s ability to deliver equitable healthcare.

Therefore, investment in data gathering is urgently required if we are to fully understand the scale of this problem. When delivering care, providers and institutions need to ask patients if they have issues swallowing solid medicines and know the implications of not offering working solutions.

In the 21st century, it is not just a patients’ physical comfort that is important but also their emotional well-being. This way, more joined-up interventions can be implemented.

2. Partnership between the public, government and pharmaceutical companies

With growing healthcare needs, increasing expectations from the health systems, and challenges of insufficient resources, it is unlikely that health services can be provided solely by a single actor. More than ever before, healthcare requires profit and social purpose to converge.

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) have traditionally taken many forms, varying in the level of participation or risk taken by different parties. We are not talking about PPPs as such, but rather, collaborative framework in which patient organizations, the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare providers work together, get closer to patients and gain deeper insights about their individual issues and not just as patients.

Although there is no-one-size-fits-all model, such a collaborative model can actually facilitate development of better therapies.

Providing medicines for marginalised or neglected demographics, such as those with swallowing problems, has been an endemic oversight in the pharmaceutical industry. This has been partly because marginal groups have not always been a viable commercial market or because companies were simply not bothered.

Given how prevalent dysphagia and other swallowing issues are, urgent action is required. There is need to join forces to pressure regulators and drug producers to address this inequality. One way is to require applicants for marketing authorisations to provide introduce alternative formats aimed at those with swallowing difficulties at launch in return for reduced regulatory fees or marketing exclusions.

It is clear that the current strategy of relying on the largesse of individual companies is not working, and a more sustainable approach is required.

Final thoughts

The vast majority of medication available today is in the form of swallowable tablets. These formats are often not appropriate for patients with dysphagia or other swallowing difficulties. Lack of availability of suitable formats for suffers predisposes these groups to sub-optimal treatments and contributes to healthcare inequalities.

If society is to equitably offer quality healthcare to all, it is necessary to take a whole person approach, recognise the many root causes of inequality, and engender system-wide action, from regulators, pharmaceutical companies, patient groups as well as healthcare workers as the immediate contact points for patients.

Sources Used

Overview of Drug Therapy in Older Adults. The Merck Mannual. (available at https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/professional/geriatrics)

Wright, D., 2014. Prescribing Medicines for Patients with Dysphagia. New York: Grosvenor House Publishing, pp.1-101.

Lisa Tews, Jodi Robinson.,2007. Dysphagia. In Kauffman T, L et al., (editors). Geriatric Rehabilitation Manual (Second Edition), Churchill Livingstone, pp 381-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-10233-2.50063-8. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780443102332500638)

Dysphagia. National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders. (available at https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/dysphagia)